Note: This story is taken from the 2025 Brickyard 400 Official Program. To read more stories like this one and learn more about what's happening this weekend, purchase your Official Program here or at the track!

You’ve surely heard of open-wheel racing icon Peter DePaolo, the man who 100 years ago won the Indianapolis 500 and became the first driver to record an average race speed faster than 100 mph.

But as a man of many other talents, that’s not all he did. In 1971, he performed “Back Home Again in Indiana” before the Indy 500. And, he had a stint as a NASCAR team owner in the 1950s that, while successful, was brief and now mostly forgotten to time.

In fact, his short time in the stock car world helped solidify two of NASCAR’s most historic teams: Holman-Moody Racing and Wood Brothers Racing. And the story of how we get there is as wild as slinging a car around Indianapolis Motor Speedway at 100 mph a century ago.

DePaolo had seven starts in “The Greatest Spectacle in Racing,” with his first coming in 1922, and his final in 1930. In 1925, he led 115 laps in his Duesenberg and collected what was then a whopping $36,150 for his win. He followed that in 1926 with a fifth-place finish, his only other top-five finish at Indianapolis.

Though he retired from full time racing in 1930, he ran one-off races in the United States and across Europe in the 30s. Then, as World War II raged on, he joined the United States Army and served with distinction, attaining the rank of lieutenant colonel.

When the war ended, and DePaolo was well into his 50s, he became a well-liked and recognizable ambassador of racing. Ford Motor Company certainly thought so, penning him as a symbol of success, Leo Levine wrote in his book “Ford: The Dust and the Glory.”

As stock car racing was gaining momentum in the 1950s, Chevrolet was experiencing lots of success in NASCAR’s early days. It introduced a new engine in its production cars following the war that was 265 cubic inches and advertised 162 horsepower.

However, the engine was created with performance and racing in mind. As time went on and development of the engine continued, independent engine tuners learned they could stretch it to 360 cubic inches with upward of 500 horsepower.

Chevrolet, it discovered, could take the youth market away from Ford by promoting this engine and its possibilities to younger audiences. As private team owners used its potential and won several NASCAR Grand National races, Chevrolet deployed an advertising agency that would make sure photos of their wins made it into the newspapers the next day.

This frustrated Ford executives, who wanted to beat their biggest Detroit rival. So, they came up with a plan to do just that.

Ford decided it was going to enter stock car racing, and the Blue Oval wanted DePaolo to be its man. In the fall of 1955, shortly after the already prestigious Southern 500, DePaolo created DePaolo Engineering, Inc. According to Levine’s book, he would own everything and make contracts with the drivers, then he would bill Ford for repayment.

This relationship essentially grew into a Ford factory race team in which Ford played an integral role in the team’s operation.

DePaolo Engineering’s first race was Oct. 9, 1955, in West Memphis, Arkansas. It wasn’t a barn burner by any means, as DePaolo’s drivers Johnny Mantz and Chuck Stevenson dropped out and finished 29th and 30th, respectively. However, it was the scene-setter DePaolo and Ford needed heading into the 1956 NASCAR season.

Leading into Daytona, the team hired eventual NASCAR legend Fireball Roberts to drive one of its cars, but it still had another seat to fill. Red Vogt, a car builder who ran the team’s operations at the time, had the idea to reach out to a driver he knew named Ralph Moody and offer him the ride. Moody, as Levine wrote, was astounded at the opportunity and accepted.

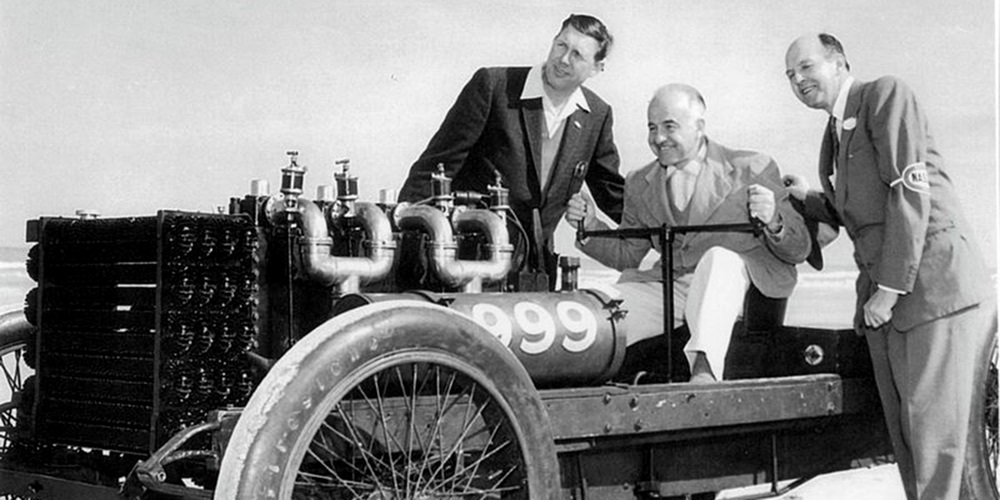

Daytona Speedweeks, then still on the beach, were filled with challenges and friction as DePaolo Engineering and Ford navigated roles and performance in their first trip to Daytona together. Still, they were able to pull together a 1-2 finish in the convertible race with Curtis Turner winning and Roberts coming in second. On Sunday in the Grand National event, Moody drove to third.

The next couple months, however, did not go in DePaolo and Ford’s direction. Chrysler/Dodge went on to win the next 16 races in NASCAR. Ford and DePaolo were frustrated at their lack of success. Lucky for them, opportunity came knocking.

In May 1956, a man by the name of John Holman arrived at DePaolo’s Long Beach race shop. As a longtime California resident, DePaolo insisted part of his race team operated out west. Holman was known as a truck driver who delivered parts to race teams but had a wealth of racing knowledge. He was out of a job and looking for work.

DePaolo agreed to bring him on and send him out east to the team’s shop in Charlotte, North Carolina. According to Levine, Holman’s goal was to run Ford’s eastern stock car operation, and that he did.

As 1956 went on, DePaolo Engineering and Ford were in a good groove. They scored a win in the Southern 500 with Turner behind the wheel, and 1957 was setting up to be the best year yet for the still new team.

Moody, who was already well known for his ability to set up a car, was elevated to an engineering role within the team. Holman was running the East Coast shop in Charlotte, which focused on NASCAR and drivers Roberts, Marvin Panch and Bill Amick. Meanwhile, DePaolo’s Long Beach operation focused on USAC’s stock car division and featured drivers Troy Ruttman, Stevenson and Jerry Unser.

DePaolo Engineering still operated as the de facto Ford factory team. However, there were private race teams that raced Fords. DePaolo and Holman were known to support the private teams and drivers, usually in the form of free parts.

One of those happened to be Glen Wood, of the eventual Wood Brothers fame. Tom Jensen, the curatorial affairs manager at the NASCAR Hall of Fame, noted a story about DePaolo that expanded his influence to one of NASCAR’s other historic race teams.

He said that after a convertible race win in April 1957 at Fayetteville, North Carolina, DePaolo reached out to congratulate Wood on the victory and asked him if he needed anything. Wood responded that he needed a set of tires for the upcoming race at Richmond. DePaolo sent six tires, and Wood won that race, too.

Eventually, DePaolo would help connect Wood to Ford and land Wood Brothers Racing as one of Ford’s premier teams. Without DePaolo helping him them get Ford support, Jensen said, Wood Brothers Racing may not have become the historic team that it did.

“That began a steady supply of parts to Glen, which would eventually include money,” Jensen said. “But, initially starting out, it was the support he needed, the parts and pieces he needed, to keep racing. That was really what kept the Wood Brothers in the game, and now, 75 years later, they're NASCAR's oldest continually operating team.”

The early stage of the 1957 NASCAR Grand National season saw Ford win 12 of 16 races. In the convertible series, Ford won 16 of 17. Utter domination by Ford was setting in. However, something else was brewing behind the scenes.

Levine wrote that in February 1957, General Motors President Harlow Curtice brought a resolution to the Automobile Manufacturers Association that would effectively ban factory-sponsored racing teams, as well as advertising horsepower or anything to do with speed in production cars. Essentially, Levine writes, they wanted to de-emphasize racing on production vehicles.

Before, the public largely looked at a car’s styling and price before making a purchase. But with the recent emphasis on speed and racing, car buyers were taking that into account, and the management and engineering teams of auto manufacturers didn’t like where the industry was heading.

Additionally, the 1955 24 Hours of Le Mans was top of mind for many executives. That year, a ferocious crash killed more than 80 people when a car went off course and into the stands, exploding in a ball of fire.

This resolution was adopted on June 6, 1957. The last Ford-sponsored entries ran June 1, and DePaolo Engineering, Inc. was effectively closed.

DePaolo had no desire to continue as a team owner, and Holman decided he wanted to carry on the Ford racing legacy as a private team without Ford’s backing. First, he reached out to Moody to inform him of the opportunity and asked if he wanted to go in on the team with him. Moody put took a lien on his airplane, which gave him $12,000.

The two of them purchased DePaolo Engineering’s machinery and equipment on June 19, setting in motion what would become Holman-Moody Racing, one of the most historic teams in NASCAR history.

In the years to come, Holman-Moody Racing won 96 NASCAR races and two championships with some of the sport’s most historic drivers such as David Pearson, Fred Lorenzen, Mario Andretti, Dan Gurney, Bobby Allison and more. Moody was inducted into the NASCAR Hall of Fame in 2025.

Ford returned to NASCAR in the 1960s, and Holman-Moody became one of Ford’s prominent teams. Holman-Moody also supplied chassis, parts, engines and more to fellow Ford teams, creating a sharing model between teams of the same manufacturer that stock car racing hadn’t yet seen but is now prominent across the garage.

If it weren’t for DePaolo, who knows if any of that history happens.

“Without Pete DePaolo, there would be no Holman-Moody, and the Wood Brothers probably wouldn't have made it,” Jensen said. “I would say there's no question that there would be no Holman-Moody.

“The Woods have managed an incredible track record of survival and prosperity for 75 years, but there would have been no Holman-Moody. No question